When Art Holds What We Cannot

Watching Hamnet with my mother in a Santa Cruz movie theater

My mother and I stood at the self-checkout kiosk at Santa Cruz Cinema, laughing at ourselves. I had tapped my card three times before she pointed at the small sign I had somehow missed: no American Express. I swiped through my digital wallet for another card while my mother made a joke about how we used to just walk up to a person behind glass. I made a joke about how that person would have told me sooner.

We agreed, standing in front of the concession display, that next time we would sneak in our own candy. Twelve dollars for a box of Milk Duds felt criminal. But we bought them anyway, along with a Diet Pepsi to share, the way we used to when I was a kid. Back when we would go to the movies to escape. Back when sitting quietly next to each other made more sense than talking.

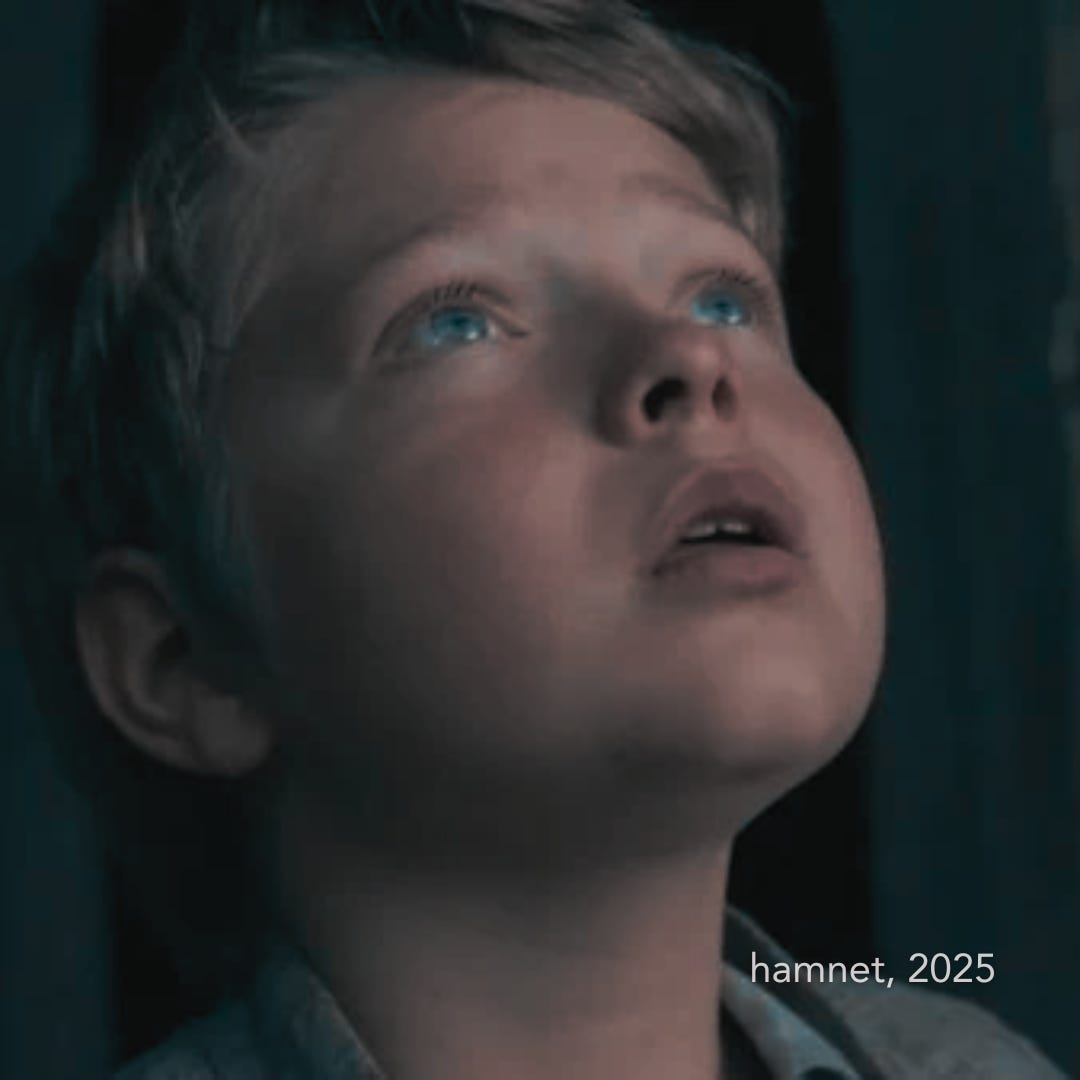

My mother had wanted to see Hamnet, Chloé Zhao’s first feature since Nomadland. As I settled into the leather reclining chairs, chewing too loudly on the caramel-chocolate candies, I didn’t think much of the name, even as the opening credits shared that Hamnet was another spelling for Hamlet. I didn’t see the relevance. This movie makes Shakespeare disappear.

It starts like most historical fiction movies my mother and I have loved to indulge in over the years. The smitten handsome Latin tutor falling for the young woman who prefers the forest and a hawk as company over the mediocrities of society.

They fall into blind love and romantic bliss. Jessie Buckley plays Agnes (the name Maggie O’Farrell gives Anne Hathaway in her novel) with a ferocity that makes Paul Mescal’s Will seem almost peripheral. He scribbles away on parchment paper, drinking too much late at night while his new wife grows with the child that was the catalyst for their marriage.

Every time Will appeared on screen, I felt his not-quite-hereness. The way his body was in the room but his mind was somewhere else. His scenes with Buckley vibrate with the tension of two people who love each other and cannot reach each other. The film does not judge him for this. It does not judge Agnes for her fury either. It holds them both, the way grief holds contradictions without resolving them.

But this wasn’t a love story between man and woman, per se. It is a story about how a child can be alive one moment and gone the next, and how that loss is processed between them: a pragmatic and an artist.

With one healthy eldest daughter, Agnes becomes pregnant again, giving birth to twins. The first baby cries. A boy. The second, a girl, does not breathe.

Everything in me tightened. My eyes were already welling before my mother grabbed my hand. Sudden, her cold fingers wrapping around mine, as if anticipating a reaction from me.

Agnes questions the midwife who walks off screen, the camera barely panning but the entire scene shifting: “Why is she not screaming?”

And I thought: I have been that woman.

Waiting for the scream you fear will not come. Holding your breath to hear that everything is okay. Refusing anything other than patience, because panic will not bring a child into the world. Waiting. Watching. Willing breath into a body that has not yet decided to stay.

Sitting there with my mother’s hand in mine, I thought of my youngest. I still remember waking in a silent delivery room, my voice gone as I screamed, Where is she? How I ran down the hallway, the floor cold under my feet, the lights too bright after the darkness of the delivery room, bleeding down my inner thighs, one thought amplified above all: Is she breathing?

I found her behind glass. Full of tubes. So small. My body will never forget the feeling of walking into that room.

She is turning seven this month. To my delight, she’s asked for books for her birthday.

When the child on screen suddenly inhaled, I was overwhelmed in the dark theater with a sudden urge to be home with her. To listen to her pronounce words for the first time. To watch her turn pages with a curiosity that matches my urge to fill them.

We would lay in the bed I’ve had since I was seven, the same bed my mother got for me from an antique shop she bought on layaway. Under an old quilt whose corner has hand stitching that reads, Love, Mom xoxo 1992, I would revel in the quiet miracle of her being here, breathing, despite it all.

Like the infant on the screen, she survives. Agnes saves her. I was bawling as the little being took her first quiet breaths. But so was everyone else.

As the children grow older, Agnes becomes convinced she is cursed with only two children beside her on her death bed, and that her daughter, the youngest twin, is the one tethered to this belief.

But it is the son who is lost.

Later in the film, when plague arrives, the girl gets sick with the pestilence. But it is the boy who tricks death into taking him instead, to be brave for his father, who is away in London creating a play.

Hamnet, eleven years old, dies a horrible death in her arms, while the daughter Agnes spent years protecting lives. The child she never thought to fear for dies.

My heart locked around the unbearable luck of raising children in an era where a simple vaccination could have prevented all of it. The unbearable luck of not having to choose which one to save. Of not having to imagine either of them gone.

But the film made me imagine it anyway.

My mother whispered, taking another sip of soda, that she didn’t expect this movie to be so heavy. I agreed, wondering if we would have braved this show if we knew this would be the experience. But I needed this. To witness a mother I could relate to in my darkest moments. More so, sitting alongside my mother.

I was so deep in Agnes’s story that I did not associate Will with Shakespeare until the final scene. And surprised by what I recognized in that moment.

Agnes, unaware of the plot of her husband’s play, which she learns is named after their son, walks defiantly into the Globe Theatre. Confused how he could use their son’s name. Angry at the actors for portraying her loss. But then she sees how her husband’s grief transformed into Hamlet.

When she finally understands what he has been doing with all those words, what he has made of their son’s death, I felt the floor shift beneath me.

At Hamlet’s death, Agnes sees his grief transformed into a play. She sees how his pain touches an audience, how it allows grief to be held collectively, how it gives him a way not to be alone in it. Something in her softens. Something in both of them does. It is not resolution. It is recognition.

For two hours, Will is just a father who leaves, a husband who cannot stay present, a man who processes by escaping into language while his wife processes by staying. The reveal is not a twist. It is a recontextualization. Everything you have watched becomes something else.

I had only previously related to Agnes. To the mother who stays. To the witness who holds everything while someone else turns it into art.

But now, I related to Will.

To the way he secluded. To the way he wrote. To the way he obsessed over thought and plot and questions and sadness. Writing was not expression. It was survival.

I have known this about myself since I learned to write.

I am the one who escapes into language. Sometimes not quite in the room, even when I am standing in it. My mind living too many timelines to know which one to prioritize. I process by writing while my husband, my mother, my daughters stay present with what I am still learning to hold.

Sitting next to my mother, watching her watch that scene, I understood.

She had already been Agnes. She had already been the one in the audience, witnessing me turn my breaking into art, not knowing if it was healing or hemorrhaging, trusting it was both.

A few years before, I had written a chapter about the day my youngest was born.

I wrote it as a vignette to be performed. Radiohead’s “High and Dry” kept cycling through my mind as I wrote, as I tried to make sense of what had happened to me, to us. When I finally decided to perform the piece, I hosted a home concert where I told the band to play Rosie Carney’s 2020 rendition and to keep playing until I stopped reading.

Forty strangers stood in the room waiting for me to speak. My husband near the back. My daughters asleep in the next room with a babysitter. My mother in the middle of the room, tears already forming behind the reflection in her glasses. She did not know what she was about to witness.

I sat barefoot on a chair in the center of the living room.

I read as the music played for fifteen minutes. The song felt like eternity because for me it is. A song that never stops playing, along with all the others that make up the soundtrack of my life. At one point, I dropped the microphone and just yelled, FUCK. I never looked up. I didn’t stop until I looked up at the plastered ceiling and asked, How the fuck did I get here?

I looked up and the room was in tears.

You may watch my performance of High & Dry from How the Fuck Did I Get Here? on Youtube here.

My mother stood in the center of them all. Her lips pursed the way they get when she’s overwhelmed with pride. Watching me transform my pain into something I could survive. Watching me bleed onto the page in front of strangers, in front of family, in front of her. She did not know, walking into that performance, that she would become a witness to her daughter’s unraveling. That in the story, she would also have to take responsibility for the character I wrote of her. That she would have to sit there and hold it. That she would see, finally, what I had been carrying since the day I brought her granddaughter home.

Like Agnes standing in the audience of Hamlet, suddenly laughing, understanding her husband’s grief was real, feeling closure and relief, turning tragedy into comedy, healing collectively.

Just like we were all doing together in the theater, on a Wednesday afternoon in downtown Santa Cruz.

The credits rolled to no applause, but no one moved to leave their seats right away. We lifted the recliner seats back upright, moved the trays forward, and agreed that we should come to the theaters more often.

As we slowly filed out, the others who braved such an afternoon of their own emotional journey would not know the cost of those tickets for my mother and me. Not just the $16.50 matinee price with her senior discount. Not the Diet Pepsi or the Milk Duds. The cost of a movie ticket is more than what you pay at the kiosk.

Sometimes it is what you are willing to feel. What you are willing to sit with. Who you are willing to sit beside.

We walked outside into the cool coastal air. The street was busy with holiday shoppers. I left through the theater glass doors a mother who has brushed up against death, a writer still searching for the words for a story too large to hold, a daughter still mending from the heartbreak of the life my mother brought me into.

Across the street was Bookshop Santa Cruz. I remembered my youngest wanted The Princess in Black for her birthday. The child who almost didn’t breathe, asking now for words on pages. A calling I shared at her age. She loves that I write. She asks me all the time why I put a bad word in my book’s title. I tell her someday she’ll understand.

“Come on,” I said to my mother, linking arms. “Let’s go to the bookstore.”

“Like we used to,” she said, smiling.

And we walked.

About the Author

Alisa Sieber is a writer, veteran, and founder of Chez Serendip, a creative sanctuary and artist residency tucked in the redwoods of Scotts Valley, California. She is the author of How the Fuck Did I Get Here? (HTFDIGH) and How the Fuck Did We Get Here? (HTFDWGH), twin series of radical self-inquiry and journalism disguised as personal essay.

Her work bridges the intimate and the systemic, tracing how individual reckoning exposes collective collapse. Through storytelling rooted in lived experience, she examines generational cycles, motherhood, militarism, creativity, and the uncomfortable truths that surface when we stop looking away.

As a contributor to The 831, Alisa covers arts and culture through the lens of creative resistance, local storytelling, and the power of discomfort to wake us up.

Connect

✉️ Email: alisa@chezserendip.com

🧠 Substack: alisasieber.substack.com

📸 Instagram: @alisa.sieber

▶️ YouTube: @writingbyalisa

Read More Film Writing by Alisa Sieber

Alisa’s film criticism lives at the intersection of art, memory, and resistance. Rather than reviewing films as products, she approaches cinema as a site of reckoning, asking what a story reveals about power, survival, and the bodies watching it.

If this piece resonated, you may also want to read Make Stories Dangerous Again, a film review on Fucktoys.

Additional Arts & Culture pieces can be found at The 831, where Alisa covers film, festivals, and creative rebellion through a deeply local lens.

Stories aren’t meant to be consumed. They’re meant to be sat with.

About Santa Cruz Cinema

Santa Cruz Cinema is an independent, locally owned movie theater located in downtown Santa Cruz, just off Pacific Avenue. Known for its intimate atmosphere and thoughtfully curated screenings, the cinema offers a place to experience films the way they’re meant to be seen, in the dark, alongside neighbors and strangers, without distraction.

📍 1405 Pacific Ave, Santa Cruz, CA 95060

📞 (831) 291-9728

🌐 www.santacruzcinema.com

With a community-forward spirit and a mix of mainstream and independent films, Santa Cruz Cinema remains one of the city’s quiet cultural anchors, a place where stories unfold collectively.

Film Information: Hamnet

From Academy Award®–winning writer and director Chloé Zhao, Hamnet tells the powerful love story that inspired Shakespeare’s timeless masterpiece, Hamlet. Adapted from Maggie O’Farrell’s acclaimed novel, the film centers grief, marriage, and loss through an intimate, human lens.

Now Playing at Santa Cruz Cinema

Format: Digital

Showtimes:

11:00 am · 1:45 pm · 4:30 pm · 7:15 pm · 10:00 pm

Dates:

Friday, December 19

Saturday, December 20

Sunday, December 21

Monday, December 22

Tuesday, December 23

Wednesday, December 24

(Showtimes subject to change. Check the theater website for current listings.)

About The 831

The 831 is an independent journalism collective serving California’s Central Coast, including Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito counties. Born after the collapse of local media, The 831 exists to restore proximity, accountability, and creative rebellion through storytelling.

We believe journalism should feel human, lived-in, and rooted in place. Our stories are written by people who live here, who know the tide, the traffic, and the weight of history carried in small moments.

From breaking news to personal essays, from arts and culture to environmental reporting, The 831 documents the creativity, contradictions, and courage of the Central Coast.

No algorithms. Just people telling the truth about where they live.